Sunlight poured through the picture windows at the Washington Forest Health Collaborative Summit where collaborative members discussed changes to Federal Forest Policy under the new administration. Photo: Jenna Knobloch/Sustainable Northwest

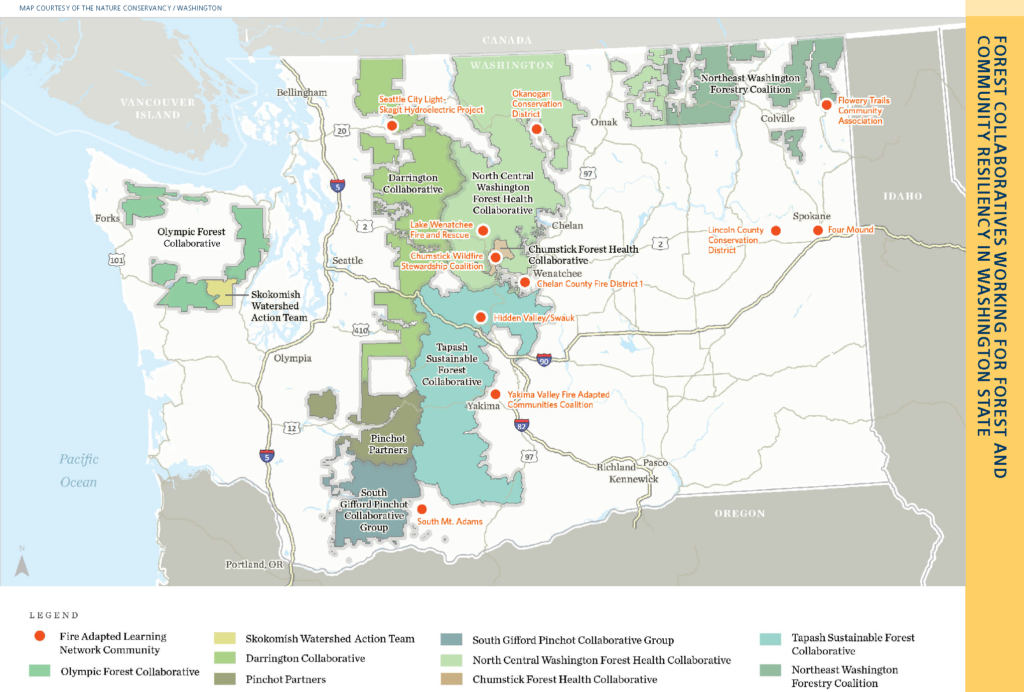

On a superb late fall day, members of the Chumstick Wildfire Stewardship Coalition (CWSC) joined seven other collaboratives in Ellensburg for two days at the Washington Forest Health Collaborative Summit. This group of collaboratives has been meeting over the course of the last four years to find common themes, solve barriers to restoration and speak with a unified voice to and with key decision-makers in our State’s capitol, Olympia.

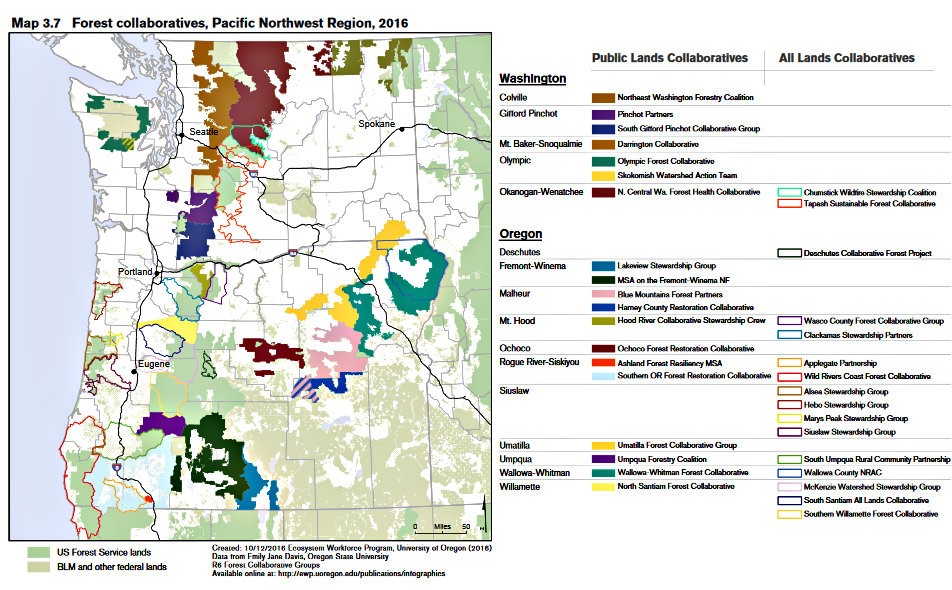

Collaboratives can be one of the most effective means to boost landscape restoration and will be key in supporting the newly unveiled Washington Department of Natural Resources 20-Year Forest Health Strategic Plan that was created collaboratively with more than 33 organizations and agencies to “maximize effectiveness of forest health treatments by coordinating and prioritizing forest management activities across large landscapes… to restore our forests; to ensure reduced threat of wildfire; and to provide abundant wildlife habitat, clean water, economic opportunities and thriving communities”. A major objective of forest health collaboratives is to increase the pace and scale of forest restoration. To this end, our forest health collaboratives continue to work with Forests to plan and implement new projects. These groups have been successful over the past few years developing and securing funding for capacity through the National Forest Foundation’s Community Capacity and Land Stewardship Program, using retained receipts from stewardship sales and are looking forward to gains with anticipated USFS and BLM Good Neighbor Authority projects.

The CWSC, both a forest health collaborative and an active Washington Fire Adapted Community Learning Network (WAFAC) member, consciously decided to take a different track. Our collaborative public lands project sits entirely within the Leavenworth Community Wildfire Protection Plan (CWPP) boundary; its stated purpose and need is to reduce the risk of catastrophic fire within the wildland urban interface (WUI). The CWSC continues to tend, fret and retool the existing decision but has not moved on to spearhead other projects within the Okanogan-Wenatchee National Forest to ensure that we meet our primary mission within the Leavenworth CWPP boundaries. In discussing metrics for success, the CWSC may not continue to “accrue” large acres of public lands treated. However, landscape restoration must include the WUI and it is complicated — it necessitates private lands and it requires, for lack of a more refined term, winning the hearts and minds of our community. Giving the keynote address at the summit, Washington’s Commissioner of Public Lands, Hilary Franz, acknowledged that private lands play a critical role in the forest health strategic plan.

So how does a very localized community effort fit into agency and non-governmental driven landscape restoration strategies in the WUI? I believe that it may fall to WAFAC members, their partners, and community ‘spark plugs’, to take up the banner. Fire adapted community practitioners know this “hearts and minds” argument. We know that investment magnifies – that private landowners taking or not taking action is matched by their neighbors. We know that landowner assistance programs not only feed local contractors but also place chainsaws and chippers in the hands of small private forest owners. We’ve heard again and again of a generational gap, of the loss of a forest culture and woods know-how, of the concern about working forest land conversion. Fire adapted community organizations have the unique ability to re-engage the populace, to create the grass-root spark plugs that will carry the mantle of rebuilding a culture of forest health.

Derek Churchill (University of Washington), one of our state’s foremost forest health scientist and forest collaborative proponents, brought some nuance to this point during concluding remarks at the summit. He stressed that we don’t fully know the extent that our forests will be altered in the years to come and forest health will require social institutions that are resilient and can change. Forest health collaboratives will need their local communities to be brought along, step by step, as restoration strategies develop and change. At the Summit, there was much encouragement and support for the themes of community resiliency, landowner assistance and working family forests. I would venture, after participating in these two days of discussion, that private lands and landscape restoration in the WUI need a stronger voice in the current forest health collaborative discussion. Washington’s Fire Adapted Communities are uniquely poised to step up to this challenge, but will need to create and advocate for the capacity to do so.